SOLID is an acronym for five key principles of Object Oriented Design (OOD) introduced by Uncle Bob.

- Single Responsibility Principle.

- Open-Closed Principle.

- Liskov Substitution Principle.

- Interface Segregation Principle.

- Dependency Inversion Principle.

These principles aim to make software design more understandable, flexible, testable and maintainable.

In this post I will try to explain each one of them using code examples.

Single Responsibility Principle

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) states that a class should have only one reason to change. In other words, a class should only do one thing.

🚫 Bad Practice (Violating SRP)

class UserManager {

void saveUser(String name) {

print("Saving user: $name");

}

void sendEmail(String email) {

print("Sending email to $email");

}

void generateReport() {

print("Generating user report...");

}

}

❌ Problems:

UserManagerdoes too many things (saving users, sending emails, generating reports).- If we change the email-sending logic, we must modify

UserManager, which should only manage users. - The class is harder to maintain and less reusable.

✅ Good Practice (Following SRP)

class UserRepository {

void saveUser(String name) {

print("Saving user: $name");

}

}

class EmailService {

void sendEmail(String email) {

print("Sending email to $email");

}

}

class ReportGenerator {

void generateReport() {

print("Generating user report...");

}

}

When Not to Split

If multiple methods within a class all serve a single responsibility, splitting isn’t necessary. For example:

class UserRepository {

void addUser(String name) {

// Logic to add user

}

void deleteUser(String name) {

// Logic to delete user

}

void updateUser(String name) {

// Logic to update user

}

}

Here, all methods pertain to user data management, so the class aligns with SRP.

The goal of SRP is to ensure that a class has one reason to change. It’s not about limiting the number of methods but about cohesive responsibilities. If methods serve different purposes, consider separating them to enhance code clarity and maintainability.

Open-Closed Principle

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP) states that:

A class should be open for extension but closed for modification.

This means:

- You should be able to add new functionality without modifying existing code.

- Instead of modifying a class, extend it (inheritance) or use interfaces (polymorphism).

🚫 Bad Example (Violating OCP)

Imagine we have a DiscountCalculator that calculates discounts based on customer type:

class DiscountCalculator {

double calculateDiscount(String customerType, double price) {

if (customerType == "Regular") {

return price * 0.1;

} else if (customerType == "VIP") {

return price * 0.2;

} else {

return 0; // No discount for unknown types

}

}

}

❌ Problems:

- If we want to add a new customer type (e.g.,

Gold), we must modifyDiscountCalculator, violating OCP. - This makes the code harder to maintain and scale.

✅ Good Example (Following OCP)

We use polymorphism (abstraction) to allow extension without modifying existing code.

// Abstract class (Open for extension)

abstract class DiscountStrategy {

double getDiscount(double price);

}

// Concrete implementations (Closed for modification)

class RegularDiscount implements DiscountStrategy {

@override

double getDiscount(double price) => price * 0.1;

}

class VIPDiscount implements DiscountStrategy {

@override

double getDiscount(double price) => price * 0.2;

}

// New discount type (extended without modifying existing code)

class GoldDiscount implements DiscountStrategy {

@override

double getDiscount(double price) => price * 0.3;

}

// High-Level Class (Depends on Abstraction)

class DiscountCalculator {

final DiscountStrategy discountStrategy;

DiscountCalculator(this.discountStrategy);

double calculate(double price) {

return discountStrategy.getDiscount(price);

}

}

void main() {

var regular = DiscountCalculator(RegularDiscount());

var vip = DiscountCalculator(VIPDiscount());

var gold = DiscountCalculator(GoldDiscount());

print("Regular discount: ${regular.calculate(100)}"); // 10

print("VIP discount: ${vip.calculate(100)}"); // 20

print("Gold discount: ${gold.calculate(100)}"); // 30

}

✅ Why is this better?

- Open for extension: We can add new discount types without modifying existing code.

- Closed for modification: The

DiscountCalculatorclass does not change when we add new discount types. - Easier to maintain and test.

- Less prone to errors, editing existing code may generate unexpected bugs.

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

The Liskov Substitution Principle states that:

- A subclass should be substitutable for its superclass without breaking the program.

- If a subclass modifies the behavior of a superclass in a way that changes how it is used, it violates LSP.

Example: Bird Hierarchy

Violation of LSP:

Consider a Bird class with a fly method and a subclass Penguin:

class Bird {

void fly() {

print('Flying');

}

}

class Penguin extends Bird {

@override

void fly() {

throw Exception("Penguins can't fly!");

}

}

Here, substituting a Penguin for a Bird can cause runtime exceptions:

void makeBirdFly(Bird bird) {

bird.fly();

}

void main() {

Bird sparrow = Bird();

makeBirdFly(sparrow); // Flying

Penguin penguin = Penguin();

makeBirdFly(penguin); // Exception: Penguins can't fly!

}

Adherence to LSP:

To adhere to LSP, we can redefine the class hierarchy:

abstract class Bird {

void move();

}

class FlyingBird extends Bird {

@override

void move() {

fly();

}

void fly() {

print('Flying');

}

}

class Penguin extends Bird {

@override

void move() {

swim();

}

void swim() {

print('Swimming');

}

}

Now, substituting FlyingBird or Penguin for Bird doesn’t cause unexpected behavior:

void makeBirdMove(Bird bird) {

bird.move();

}

void main() {

FlyingBird sparrow = FlyingBird();

makeBirdMove(sparrow); // Flying

Penguin penguin = Penguin();

makeBirdMove(penguin); // Swimming

}

Interface Segregation Principle:

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) states that “clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use.” In other words, rather than having one large, “fat” interface, it’s better to split it into smaller, more specific ones. This way, classes can implement only the methods they need, making the system more modular and easier to maintain.

Below are four examples in Dart: two that violate ISP and two that adhere to it.

Violating Examples

Example 1: MultiFunctionDevice Interface

In this example, a single interface forces classes to implement methods they don’t need.

abstract class MultiFunctionDevice {

void printDocument(String doc);

void scanDocument(String doc);

void faxDocument(String doc);

}

class OldPrinter implements MultiFunctionDevice {

@override

void printDocument(String doc) {

print("Printing: $doc");

}

// OldPrinter doesn't support scanning

@override

void scanDocument(String doc) {

throw UnimplementedError("Scan not supported.");

}

// Nor does it support faxing

@override

void faxDocument(String doc) {

throw UnimplementedError("Fax not supported.");

}

}

Why It Violates ISP:

OldPrinter is forced to implement scanDocument and faxDocument even though it only needs to print. Clients using OldPrinter might mistakenly try to call these methods, leading to runtime errors.

Example 2: AnimalActions Interface

Here, an interface combines unrelated actions, forcing a class (like Dog) to implement a method it doesn’t need.

abstract class AnimalActions {

void run();

void fly();

void swim();

}

class Dog implements AnimalActions {

@override

void run() {

print("Dog is running");

}

// Dogs can't fly, yet they must implement this method.

@override

void fly() {

throw UnimplementedError("Dog can't fly.");

}

@override

void swim() {

print("Dog is swimming");

}

}

Why It Violates ISP:

The Dog class is forced to implement fly(), even though flying isn’t a behavior applicable to dogs. This leads to unnecessary boilerplate and potential runtime issues.

Adhering Examples

Example 1: Segregated Device Interfaces

By splitting the responsibilities into separate interfaces, each class only implements what it needs.

abstract class Printer {

void printDocument(String doc);

}

abstract class Scanner {

void scanDocument(String doc);

}

abstract class Fax {

void faxDocument(String doc);

}

class SimplePrinter implements Printer {

@override

void printDocument(String doc) {

print("Printing: $doc");

}

}

// A multifunction device can choose to implement multiple interfaces:

class AdvancedMultiFunctionDevice implements Printer, Scanner, Fax {

@override

void printDocument(String doc) {

print("Printing: $doc");

}

@override

void scanDocument(String doc) {

print("Scanning: $doc");

}

@override

void faxDocument(String doc) {

print("Faxing: $doc");

}

}

Why It Adheres to ISP:

Each interface is small and focused. A simple printer only implements Printer, while a multifunction device can implement additional interfaces as needed.

Example 2: Vehicle Interfaces

Imagine vehicles that have different modes of operation. Instead of a single “Vehicle” interface with every possible method, we create specific ones.

abstract class Drivable {

void drive();

}

abstract class Sailable {

void sail();

}

abstract class Flyable {

void fly();

}

class Car implements Drivable {

@override

void drive() {

print("Car is driving");

}

}

class AmphibiousCar implements Drivable, Sailable {

@override

void drive() {

print("Amphibious car is driving");

}

@override

void sail() {

print("Amphibious car is sailing");

}

}

class Airplane implements Flyable {

@override

void fly() {

print("Airplane is flying");

}

}

Why It Adheres to ISP:

Each vehicle class implements only the interfaces relevant to its capabilities. A Car doesn’t need to implement sail() or fly(), and an Airplane isn’t forced to implement unrelated methods.

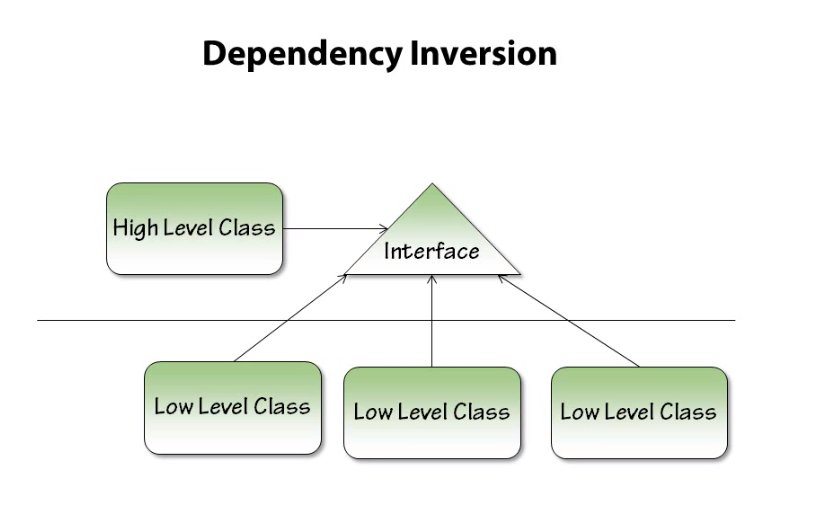

Dependency Inversion

High-Level vs. Low-Level Modules in DIP

In the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP), we classify modules as high-level or low-level based on their role in the system.

| Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Level Module | Defines core business logic. It should not worry about implementation details. | A PaymentService that processes transactions. |

| Low-Level Module | Provides implementation details. It performs specific operations (e.g., database access, API calls). | A PayPalPaymentProcessor that handles actual payment transactions. |

❌ Bad Example (Violating DIP)

Here, the high-level PaymentService directly depends on the low-level PayPalPaymentProcessor:

class PayPalPaymentProcessor {

void pay(double amount) {

print("Paying $amount using PayPal");

}

}

class PaymentService {

final PayPalPaymentProcessor processor;

PaymentService(this.processor);

void processPayment(double amount) {

processor.pay(amount);

}

}

void main() {

var processor = PayPalPaymentProcessor();

var paymentService = PaymentService(processor);

paymentService.processPayment(100);

}

❌ Problems:

PaymentServicedepends directly onPayPalPaymentProcessor. If we want to switch to Stripe, we must modifyPaymentService.- Tightly coupled code, making it hard to test and extend.

✅ Good Example (Following DIP)

We introduce an abstraction (interface) so that PaymentService depends on an abstract contract rather than a specific implementation.

// Abstraction (Interface)

abstract class PaymentProcessor {

void pay(double amount);

}

// Low-Level Modules (Implementing the Interface)

class PayPalPaymentProcessor implements PaymentProcessor {

@override

void pay(double amount) {

print("Paying $amount using PayPal");

}

}

class StripePaymentProcessor implements PaymentProcessor {

@override

void pay(double amount) {

print("Paying $amount using Stripe");

}

}

// High-Level Module (Depends on Abstraction)

class PaymentService {

final PaymentProcessor processor;

PaymentService(this.processor);

void processPayment(double amount) {

processor.pay(amount);

}

}

void main() {

var processor = PayPalPaymentProcessor(); // Can easily switch to StripePaymentProcessor

var paymentService = PaymentService(processor);

paymentService.processPayment(100);

}

✅ Improvements:

PaymentServicedepends on an abstraction (PaymentProcessor), not a concrete class.- Now we can easily switch from PayPal to Stripe without modifying

PaymentService. - The code is more flexible, reusable, and testable.

- the code is now more extensible you can add as many payment methods as you want without editing existing ones.

Bad (Violates DIP):

High-level modules depend directly on low-level modules.

Good (Follows DIP):

Both high-level and low-level modules depend on abstractions.

Comparison table for the five SOLID principles:

| Principle | What It States | Primary Focus | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Responsibility | A class should have one reason to change—it should do one thing and do it well. | Separation of concerns; high cohesion. | Easier maintenance, increased clarity, and reusability. |

| Open-Closed | Software entities should be open for extension but closed for modification. | Extensibility via abstraction and polymorphism. | Safer addition of new functionality without modifying existing code. |

| Liskov Substitution | Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types without affecting the correctness of the program. | Proper inheritance and ensuring that derived classes maintain base class behavior. | Robust and reliable polymorphism and system behavior. |

| Interface Segregation | Clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use; instead, create smaller, more specific interfaces. | Designing minimal and focused interfaces. | Reduced coupling, cleaner APIs, and easier refactoring. |

| Dependency Inversion | High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules; both should depend on abstractions. Details should depend on abstractions, not vice versa. | Managing dependencies and decoupling code. | Increased flexibility, easier testing, and better code maintainability. |